What is vitreomacular traction?

The middle of the eye is filled with a substance called vitreous. In the healthy, young eye, this clear, gel-like substance is firmly attached to the retina and the macula by millions of microscopic fibers. As the eye ages, or as a result of eye disease, the vitreous shrinks and pulls away from the retina. The vitreous, over time, separates completely from the retina. This is called a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) and is usually a normal part of aging. It happens to most people by age 70.

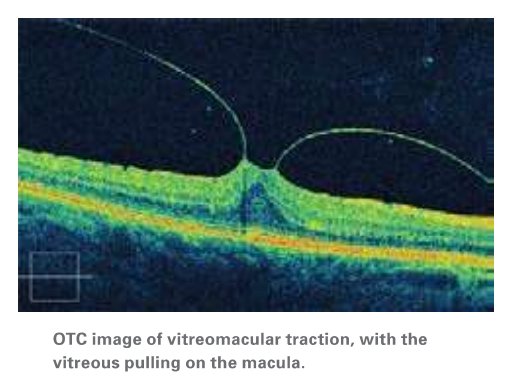

In some people with PVD, the vitreous doesn’t detach completely. Part of the vitreous remains stuck to the macula, at the center of the retina. The vitreous pulls and tugs on the macula, causing vitreomacular traction (VMT). This can damage the macula and cause vision loss if left untreated.

What causes vitreomacular traction?

VMT is usually caused by part of the vitreous remaining stuck to the macula during a posterior vitreous detachment.

In healthy eyes, VMT is not common. People with certain eye diseases may be at a higher risk for VMT, including those with:

- high myopia (extreme nearsightedness)

- age-related macular degeneration (or AMD, a breakdown of tissues in the back of the eye)

- diabetic eye disease (disease that affects the blood vessels in the back of the eye)

- retinal vein occlusion (a blockage of veins in the retina)

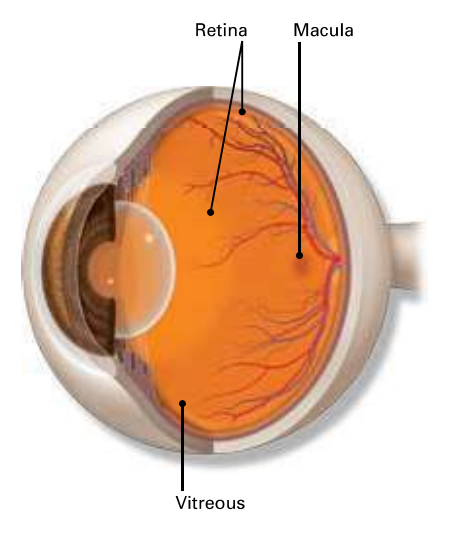

Retina: Layer of cells lining the back wall inside the eye. This layer senses light and sends signals to the brain so you can see.

Macula: Small but important area in the center of the retina. You need the macula to clearly see details and colors of objects in front of you.

Vitreous: Clear, gel-like substance that fills the inside of your eye. The vitreous helps the eye maintain its shape and also transmits light to the retina.

What are symptoms of vitreomacular traction?

The most common symptoms of VMT include:

- distorted vision that makes a grid of straight lines appear wavy, blurry, or blank.

- seeing flashes of light in your vision

- seeing objects as smaller than their actual size

These symptoms can also be a sign of another eye disease. This is why it’s important to see an ophthalmologist for an evaluation when you first notice any of these symptoms.

How is vitreomacular traction diagnosed?

To diagnose VMT, your ophthalmologist needs to look inside your eye. To do this, they may use one or more of these tests:

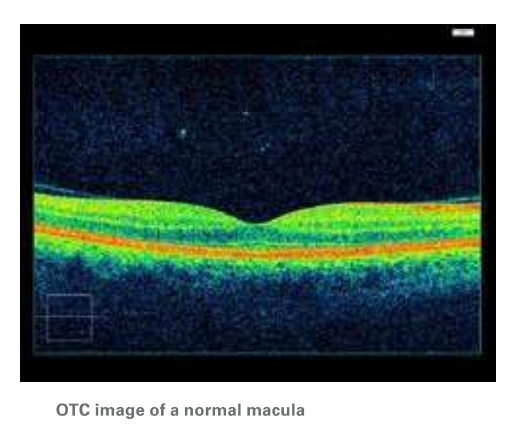

Optical Coherence Tomograhy (OCT): The OCT is an imaging test that uses light waves to take pictures of each of the retina’s layers. It can help show how damaged the macula may be.

Ultrasound scan. This imaging test uses sound waves that gives your ophthalmologist a better view of the sticking point between the vitreous and the macula.

These tests all help find out if you have VMT. They also can tell your doctor what treatment may be needed, if any.

How is vitreomacular traction treated?

After a diagnosis of VMT, there are usually three treatment options:

Observation or a “wait-and-see” approach. If your VMT is mild and not affecting your vision, treatment might not be needed. Because some cases of VMT will resolve on their own, you and your ophthalmologist may decide to observe (watch) the condition with follow-up visits. You also will be asked to monitor your vision at home each day with an Amsler grid. Your ophthalmologist will review proper use of the Amsler grid.

Surgery: Severe cases of VMT can lead to vision- threatening retinal conditions, such as:

- macular hole (when tugging of the vitreous creates a hole in the macula)

- macular pucker (when macular scar tissue builds up and distorts vision),

- or cystoid macular edema (swelling of the macula).

In these cases, a procedure called a vitrectomy may be recommended to restore the macula to its normal (lying flat) shape. The surgeon uses tiny instruments to remove the vitreous from the eye and replaces it with a saline fluid. Any scar tissue on the macula is also peeled with special instruments under a microscope. This relieves the traction that is damaging the macula.

Medication. Some people with severe cases of VMT might not be good candidates for vitrectomy surgery. A medication called ocriplasmin is a treatment option for these patients. The drug is given by intravitreal injections (injection into the center of the eye) and works by dissolving the tiny protein fibers that connect the vitreous with the macula.

Summary

Vitreomacular traction (VMT) happens when vitreous has an unusually strong attachment to the retina in the back of the eye. As the eye ages, the vitreous doesn’t detach completely from the macula as it should. The vitreous then pulls on the macula, which can damage the macula and threaten vision. Symptoms of VMT include distorted/blurry vision, seeing flashes in your vision, and seeing objects as smaller than their actual size.

Sometimes VMT goes away on its own without treatment. When VMT is more severe, it can lead to vision loss. In these cases, surgery or medication may be recommended to dislodge the vitreous from the macula and relieve the traction that threatens your vision.

If you have any questions about your eyes or your vision, speak with your ophthalmologist. He or she is committed to protecting your sight.

Get more information about VMT from EyeSmart—provided by the American Academy of Ophthalmology—at aao.org/vmt-link.